FittingRoom is an in-browser letterfitting experiment based on nonnegative matrix factorization.

What is it?

It's a very, very experimental tool for type designers who want to play with machine-assisted letterfitting. Letterfitting is the process of adjusting the distance between individual letters. Given the number of letter pairings there are, this is a tedious process – but it's an important one, because badly fitted fonts look drunk.

How does it work?

Conventional wisdom says space first, kern later, meaning: first set up left and right side bearings around each letter to make everything look okay, then make adjustments to individual pairs (the so-called kerns).

The distinction between sidebearings and kerns has two good reasons: first, it's how metal type used to work, second, it's a lot easier than fitting every pair individually (plus, it makes for smaller files, duh). Because this distinction is so practical, it's easy to overlook that it's entirely artifical and arbitrary: what matters, really, are only the distances between pairs. What if, instead of worrying about sidebearings and kerns (and how changing one will mess up ten others elsewhere), you could simply drag letters around, and your computer could figure out what you mean, and apply changes throughout the font to reflect those stylistic choices? And at the end of the process, a magical algorithm hands you a list of sidebearings and kerning values? Wouldn't that be awesome?

That's not an answer, dude. How does it actually work?

Okay. We'll have to first identify letters that are similar to one another. For example, if pairings with o have certain letter distances, then those for pairings with q are probably similar, because they're both round. People have thought of this before: Frank Blokland and Pablo Impallari have, for example; and the people who thought up OpenType kerning classes have, too. But not all letters can be placed into neat groups. What's more, groups may differ from typeface to typeface.

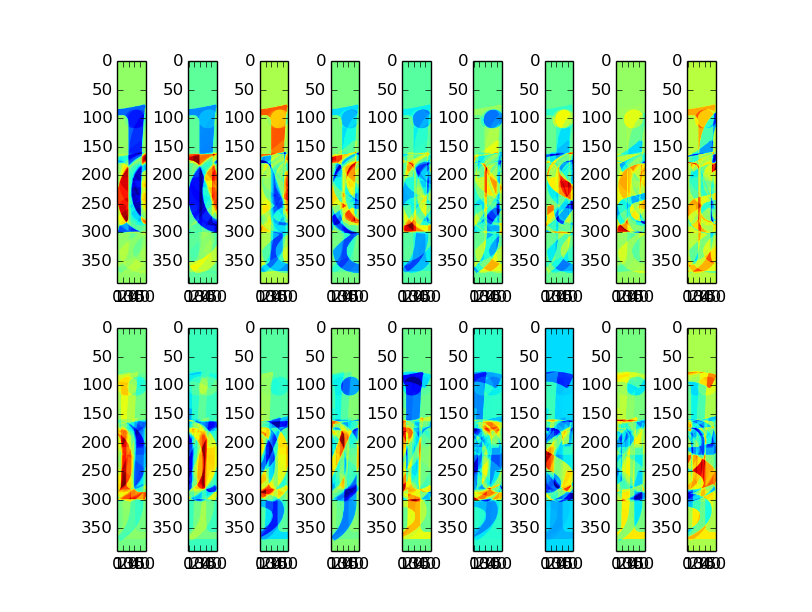

So let's embrace this haziness of real life, and resort to math. We'll use a technique called nonnegative matrix factorization. It generates for us a set of grayscale images which, kinda-sorta, represent proto-letters such that all actual letter shapes can be considered a weighted average of these images. In machine-learning speak, the images are called components or sometimes features (I'll call them the latter for now) and the weighting coefficients are, well, weights. If we limit ourselves to two or three of such features, they will look like blurry grey blobs; with more, you'll clearly recognize them as representation of letter groups (round, straight, etc.). When you use as many features as letters, each feature will be exactly one letter. You get the idea.

Wait, so instead of 26 letters you're now looking at what, five of these features or so?

Of course, because there are fewer features than letters, the weighted averages will never be completely faithful reproductions of the letters. But that's a fair price to pay.

Here's the key: instead of fitting letters, we'll fit features – in fact, we'll use separate features for left sides and right sides of the letters. Here's an example with 4 features:

a) round-ish (convex) right side

b) dented-in (concave) right side

c) round-ish left side

d) straight-ish left side

And the following distance estimates (don't worry about the term estimates ... it's, uhm, historical):

a-c: 10

a-d: 13

b-c: 5

b-d: 8

Now let's calculate the distance between x and a. Here are the weights from the NMF: xright side = 4% a + 96% b and aleft side = 28% c + 72% d. Then we can estimate the total distance between the pair by calculating (4% × 28% × a-c) + (4% × 72% × a-d) + (96% × 28% × b-c) + (96% × 72% × b-d), which is mostly b-d, but also a bit of everything else, because x isn't perfectly represented by feature b, and a isn't perfectly represented by feature d.

When you do this calculation for all pairings at once, it becomes two matrix multiplications: right-side-weights × estimates × left-side-weights^T.

Alright. You're saying, because we only use a few features – which mathematically will likely turn out to represent "round-ish", "straight-ish", etc. – we'll have much less work than fitting each of (26 × 2)² = 2704 pairings separately.

That's right!

Am I supposed to do my letterfitting on a bunch of weird blurry grayscale images?

No, that would suck. We can let you fit letters normally, within words. And when you make a change – say, you make the distance between x and a equal to 34 pixels exactly – then we can use the weights to perform the above calculation backwards, and distribute your adjustment to the underlying feature-feature estimates according to how much they represent the pair you just adjusted.

I see. Another bunch of matrix multiplications. How many features do we start with?

One! That is, one for the right sides, one for the left. Of course, with just one pair of features (which are just plain averages of all letters), all you can do is create a very rough spacing across all letter pairs. You can then increase the number of features. Each time, the nonnegative matrix factorization algorithm computes an entirely new set of features. But we'll set the weights such that your previous distance estimates are disturbed as little as possible.

In case you care, to do this we simply solve for the least-squares weights after a quick QR decomposition of a weights-weights matrix, which—

—I don't care, no.

Anyways, the point is this. By progressively increasing the number of features, you are progressively decoupling different-looking letter pairs from one another. As a result, the adjustments you make won't affect other letter pairs as much. You can go as far as you like with this, but you'll probably be fed up after, say, 8 or 9 features.

Sure. Now how do I go from a bunch of distances between these "features" to, you know, sidebearings and kerns?

You click on the blue button. This sets up a linear programming model, or LP. An LP is a big matrix of equations, which can be solved such that some sum of values is minimized. In our case, our equations represent the following: for each letter pair,

right sidebearing + kerning value + left sidebearing = pair distance computed from the feature-feature estimates.

While staying within these constraints, we'll minimize the sum of all kerning values. Because we want as little kerning throughout the font as possible, right?

Now, this isn't straightforward, because negative and positive kerns will cancel each other out, so we'll have to add—

—k, got it, done?

Done.

Actually, wait. Why did you do this in Javascript? The entire type world uses Python.

I know, and I ♥ Python, and have used it a lot in the past for numerical work.

This project was, above all, an opportunity for me to test out new stuff:

- react-redux, which turned out to be awesome; I highly recommend it for front-end work.

- ndarray. The best non-asmjs/non-GPU collection of matrix tools for JS there is. I may make a asmjs and/or GPU version of this tool in the future. For now, I can confidently say that ndarray is great, although it's still miles behind Scipy or Julia, of course.

- Linear optimization in the browser. I was disappointed to find that all available Simplex solvers in Javascript are pretty horrible. So I went ahead and transpiled the CLP solver, which is the best (libre) one around. So that is the one you're running here. I hope it works for you. Of course, without proper BLAS/LAPACK etc. it's still much slower in the browser than run natively.

Why nonnegative matrix factorization, and not PCA or some other (probably faster) decomposition?

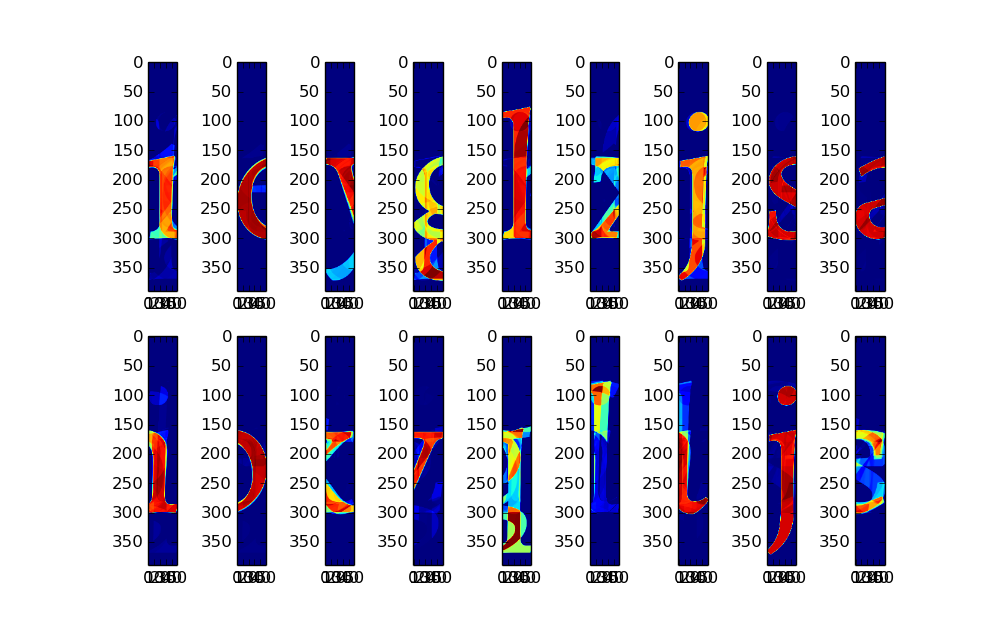

Because those other decompositions don't discriminate between negative space and ink-space, and are perfectly happy to give you features that need to be added and subtracted from each other. As a result, the features don't look at all like letter groups and more like abstract art. Here are the 9-feature PCA and NMF reductions for Alegreya:

What's next?

I think for a first experiment, the results are pretty good. You do get a ton of kerning pairs out of the optimization, but most of them are miniscule and could simply be discarded.

Now, if you wanted to turn this into a real tool, in RoboFab or whatever, you'd probably want to do some extra stuff:

- let the user adjust the geometry of the rectangles fed into NMF

- maybe not only have distances depend on feature estimates, but also on other stuff, like minimum absolute distances between letters, or distances between stems (which one might identify using e.g. Gabor filters). This would play a role in optical-size-dependent letterfitting.

- let the user specify minimum distances between certain letter pairs, which would be added to the LP model as extra constraints

- change up the objective function: maybe use the sum of the squares of the kerns (would need a different solver), or modify the objective to also (in some weighted sense) optimize the look of the font if kerning is disabled

- optimization for an OT kern table of minimal size: this is probably a more useful cost metric than the sheer sum of kerns, especially when you're serving millions of files a day ... hey, Google, I'm for hire :) (you'd probably want to use a constraint solver for this)

- incorporating it into a UI that allows you to deal with glyphs beyond

[a-zA-Z]... libre automatic MetricsMachine clone, anyone? - obviously, export the metrics into the font file – there isn't an easy way to do that from JS yet

- ... a million other things.

Can I fork this?

Please do! I don't think I'll have a ton of time to work on this in the future, but all contributions/ideas/comments are welcome :)

The code is a bit of a mess probably. Don't judge.

License is GLPv3.