|

|

|---|---|

| Travis CI | |

| Frameworks |   |

| Platform |  |

| Licence |  |

RxReduce is a Reactive implementation of the state container pattern (like Redux). It is based on the simple concepts of state immutability and unidirectionnal data flow.

Since a few years there has been a lot, I mean a LOT, of blog posts, tutorials, books, conferences about adapting alternate architecture patterns to mobile applications. The idea behind all those patterns is to provide a better way to:

- meet the SOLID requirements (Wikipedia)

- produce a safer code by design

- make our code more testable

The good old MVC tends to be replaced by MVP, MVVM or VIPER. I won't go into details about these ones as they are well documented. I think MVVM is currently the most trending pattern, mostly because of its similarities with MVC and MVP and its ability to leverage data binding to ease the data flow. Moreover it is pretty easy to be enhanced by a Coordinator pattern and Reactive programming.

Go check this project if you're interested in Reactive Coordinators (RxFlow) 👌

That said, there is at least one other architecture pattern that stands out a little bit: State Container.

One of the most famous exemple is Redux, but let's not be restrained by a specific implementation.

Some resources about state containers:

The main goals of this pattern are to:

- expose a clear/reproductible data flow within your application

- rely on a single source of truth: the state

- leverage value types to handle the state immutability

- promote functional programming, as the only way to mutate a state is to apply a free function: the reducer

I find this approach very interesting compared to the more traditional ones, because it takes care of the consistency of your application state. MVC, MVP, MVVM or VIPER help you slice your application into well defined layers but they don't guide you so much when it comes to handle the state of your app.

Reactive programming is a great companion to state container architectures because it can help to:

- propage the state mutations

- build asynchronous actions to mutate the state (for networking, persistence, ...)

RxReduce:

- provides a generic store that can handle all kinds of states

- exposes state mutation through a Reactive mechanism

- provides a simple/unified way to mutate the state synchronously and asynchronously via Actions

In your Cartfile:

github "RxSwiftCommunity/RxReduce"In your Podfile:

pod 'RxReduce'The core mechanisms of RxReduce are very straightforward:

Here is a little animation that explains the flow within a state container architecture:

- The Store is the component that handles your state. It has only one input: the "dispatch()" function, that takes an Action as a parameter.

- The only way to trigger a State mutation is to call this "dispatch()" function.

- Actions are simple types with no business logic. They embed the payload needed to mutate the state

- Only free and testable functions called Reducers (RxReduce !) can mutate a State. A "reduce()" function takes a State, an Action and returns a mutated State ... that simple. To be precise, a reducer returns a mutated sub-State of the State. In fact, there is one reducer per sub-State of the State. By sub-State, we mean all the properties that compose a State.

- The Store will make sure you provide one and only one reducer per sub-State. It brings safety and consistency to your application's logic. Each reducer has a well defined scope.

- Reducers cannot perform asynchronous logic, they can only mutate the state in a synchronous and readable way. Asynchronous work will be taken care of by Reactive Actions.

- You can be notified of the state mutation thanks to a Observable<State> exposed by the Store.

As the main idea of state containers is about immutability, avoiding reference type uncontrolled propagation and race conditions, a State must be a value type. Structs and Enums are great for that.

struct TestState: Equatable {

var counterState: CounterState

var userState: UserState

}

enum CounterState: Equatable {

case empty

case increasing (Int)

case decreasing (Int)

}

enum UserState: Equatable {

case loggedIn (name: String)

case loggedOut

}Making states Equatable is not mandatory but it will allow the Store not to emit new state values if there is no change between 2 actions. So I strongly recommand to conform to Equatable to minimize the number of view refreshes.

Actions are simple data types that embed a payload used in the reducers to mutate the state.

enum AppAction: Action {

case increase(increment: Int)

case decrease(decrement: Int)

case logUser(user: String)

case clear

}As I said, a reducer is a free function. These kind of functions takes a value, returns an idempotent value, and performs no side effects. Their declaration is not even related to a type definition. This is super convenient for testing 👍

Here we define two reducers that will take care of their dedicated sub-State. The first one mutates the CounterState and the second one mutates the UserState.

func counterReduce (state: TestState, action: Action) -> CounterState {

guard let action = action as? AppAction else { return state.counterState }

var currentCounter = 0

// we extract the current counter value from the current state

switch state.counterState {

case .decreasing(let counter), .increasing(let counter):

currentCounter = counter

default:

currentCounter = 0

}

// according to the action we mutate the counter state

switch action {

case .increase(let increment):

return .increasing(currentCounter+increment)

case .decrease(let decrement):

return .decreasing(currentCounter-decrement)

case .clear:

return .empty

default:

return state.counterState

}

}

func userReduce (state: TestState, action: Action) -> UserState {

guard let action = action as? AppAction else { return state.userState }

// according to the action we mutate the users state

switch action {

case .logUser(let user):

return .loggedIn(name: user)

case .clear:

return .loggedOut

default:

return state.userState

}

}Each of these Reducers will only handle the Actions it is responsible for, nothing less, nothing more.

RxReduce provides a generic Store that can handle your application's State. You only need to provide an initial State:

let store = Store<TestState>(withState: TestState(counterState: .empty, userState: .loggedOut))As we saw: a reducer takes care only of its dedicated sub-State. We will then define a bunch of reducers to handle the whole application's state mutations. So, we need a mechanism to assemble all the mutated sub-State to a consistent State.

We will use functional programming technics to achieve that.

A Lens is a generic way to access and mutate a value type in functional programming. It's about telling the Store how to mutate a certain sub-State of the State. For instance the Lens for CounterState would be:

let counterLens = Lens<TestState, CounterState> (get: { testState in return testState.counterState },

set: { (testState, counterState) -> TestState in

var mutableTestState = testState

mutableTestState.counterState = counterState

return mutableTestState

})it's all about defining how to access the CounterState property (the get closure) of the State and how to mutate it (the set closure).

A mutator is simply a structure that groups a Reducer and a Lens for a sub-State. Again for the CounterState:

let counterMutator = Mutator<TestState, CounterState>(lens: counterLens, reducer: counterReduce)A Mutator has everything needed to know how to mutate the CounterState and how to set it to its parent State.

After instantiating the Store, you have to register all the Mutators that will handle the State's sub-States.

let store = Store<TestState>(withState: TestState(counterState: .empty, userState: .loggedOut))

let counterMutator = Mutator<TestState, CounterState>(lens: counterLens, reducer: counterReduce)

let userMutator = Mutator<TestState, UserState>(lens: userLens, reducer: userReduce)

store.register(mutator: counterMutator)

store.register(mutator: userMutator)And now lets mutate the state:

store.dispatch(action: AppAction.increase(increment: 10)).subscribe(onNext: { testState in

print ("New State \(testState)")

}).disposed(by: self.disposeBag)Lately, Swift 4.1 has introduced conditional conformance. If you are not familiar with this concept: A Glance at conditional conformance.

Basically it allows to make a generic type conform to a protocol only if the associated inner type also conforms to this protocol.

For instance, RxReduce leverages this feature to make an Array of Actions be an Action to ! Doing so, it is perfectly OK to dispatch a list of actions to the Store like that:

let actions: [Action] = [AppAction.increase(increment: 10), AppAction.decrease(decrement: 5)]

store.dispatch(action: actions).subscribe ...The actions declared in the array will be executed sequentially 👌.

Making an Array of Actions be an Action itself is neat, but since we're using Reactive Programming, RxReduxe also applies this technic to RxSwift Observables. It provides a very elegant way to dispatch an Observable<Action> to the Store (because Observable<Action> also conforms to Action), making asynchronous actions very simple.

let increaseAction = Observable<Int>.interval(1, scheduler: MainScheduler.instance).map { _ in AppAction.increase(increment: 1) }

store.dispatch(action: increaseAction).subscribe ...This will dispatch a AppAction.increase Action every 1s and mutate the State accordingly.

If we want to compare RxReduce with Redux, this ability to execute async actions would be equivalent to the "Action Creator" concept.

For the record, we could even dispatch to the Store an Array of Observable<Action>, and it will be seen as an Action as well.

let increaseAction = Observable<Int>.interval(1, scheduler: MainScheduler.instance).map { _ in AppAction.increase(increment: 1) }

let decreaseAction = Observable<Int>.interval(1, scheduler: MainScheduler.instance).map { _ in AppAction.decrease(decrement: 1) }

let asyncActions: [Action] = [increaseAction, decreaseAction]

store.dispatch(action: asyncActions).subscribe ...Conditional Conformance is a very powerful feature.

The Store provides a way to "observe" the State mutations from anywhere. All you have to do is to subscribe to the "state" property:

store.state.subscribe(onNext: { appState in

print (appState)

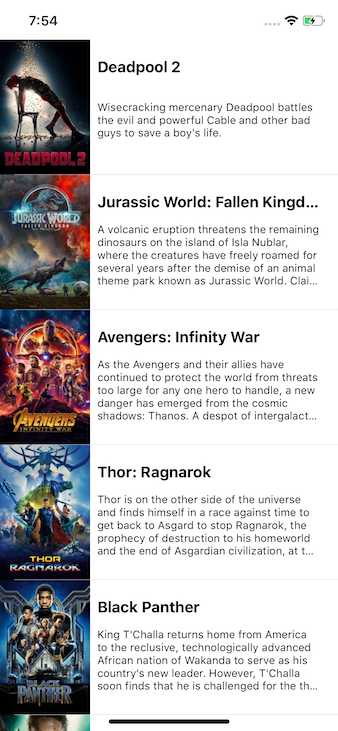

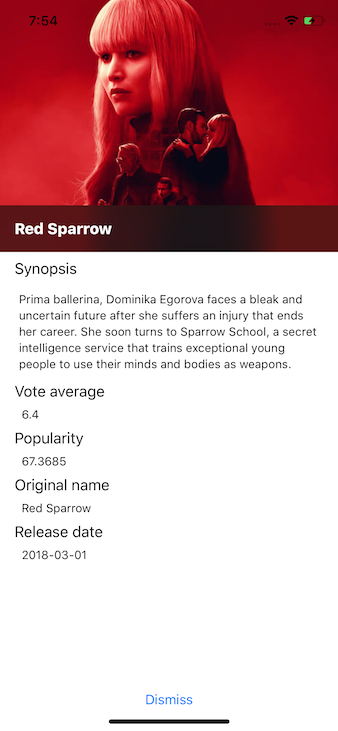

}).disposed(by: self.disposeBag)A demo application is provided to illustrate the core mechanisms, such as asynchronicity, sub states and view state rendering.

|

|

RxReduce relies on:

- SwiftLint for static code analysis (Github SwiftLint)

- RxSwift to expose State and Actions as Observables your app and the Store can react to (Github RxSwift)

- Reusable in the Demo App to ease the storyboard cutting into atomic ViewControllers (Github Reusable)