We've all been there: you've been working on the API backend, and you're happy with how it's going. You've recently completed the minimal viable product, the tests are all passing, and you're looking forward to implementing some new features. Then the boss sends you an email: "By the way, we need to let people log in via Facebook and Google; they shouldn't have to create an account just for a little site like ours."

$ pip search oauth | wc -l

278

$ pip search oauth | grep -i django | wc -l

53The bad news is that pip knows about 278 packages which deal with oauth, 53 of which specifically mention django. It's a week's work just to research the options in any depth, let alone start writing code. It might happen that you're not familiar with OAuth2 at all; I wasn't, when this situation first happened to me. So what are you supposed to do?

The good news is that OAuth2 has emerged as the industry standard for social and third-party authentication, so you can focus on understanding and implementing that standard. Let's get going, then.

Note: Though this article focuses on the Django Rest Framework, the techniques discussed are applicable to a variety of common backend frameworks. More on that later.

OAuth2 was designed from the beginning as a web authentication protocol. This is not quite the same as if it had been designed as a net authentication protocol; it assumes that tools like HTML rendering and browser redirects are available to you. This is obviously something of a hindrance for a JSON-based API, but we can work around that. First, let's go through the process as if we were writing a traditional, server-side website.

The first step in the process happens outside the application flow entirely: the project owner has to register your application with each OAuth2 provider with whom logins should be supported. During this registration, they provide the OAuth2 provider with a callback URI, at which your application will be available to receive requests. In exchange, they receive a client key and client secret. These tokens are exchanged during the authentication process to validate the login requests. Note that these tokens refer to your server code as the client, because the host is the OAuth2 provider. They aren't meant for your API's clients.

The below image currently hotlinks to an image I found on imgur, but for the article proper we should probably create our own.

The flow begins when your application generates a page which includes a button like "Log in with Facebook" or "Sign in with Google+". Fundamentally, these are nothing but simple links, each of which points to a URL like:

https://oauth2provider.com/auth?

response_type=code&

client_id=CLIENT_KEY&

redirect_uri=CALLBACK_URI&

scope=profile&

scope=email

(Line breaks inserted into the URI above for readability.)

Let's unpack that a little. You've provided your client key and redirect URI, but no secrets. In exchange, you've told the server that you'd like an authentication code in response, and access to both the 'profile' and 'email' scopes. These scopes define the permissions you request from the user, and limit the authorization of the access token you will receive.

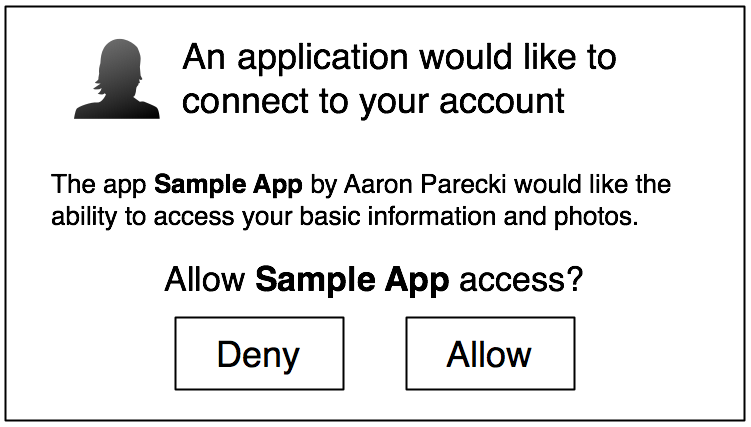

Upon receipt, the user's browser is pointed to a dynamic page the OAuth2 provider controls. The OAuth2 provider verifies that the callback URI and client key match each other before proceeding. If they do, the flow diverges briefly depending on the user's session tokens; if the user isn't currently logged in to that service, they'll be prompted to do so first. Once they're logged in, the user is presented with a dialog requesting permission to allow your application to log in.

We definitely need to re-create this image, but it's pretty much exactly what we want. To match our example here, it should say "The app Example by Toptal Blog would like the ability to access your basic profile information and email address."

Assuming the user approves, the OAUth2 server then redirects them back to the callback URI that you provided, including an authorization code in the query parameters: GET https://api.yourapp.com/oauth2/callback/?code=AUTH_CODE. This is a fast-expiring, single-use token; immediately upon its receipt, your server should turn around and make another request to the OAuth2 provider, including both the auth code and your client secret:

POST https://oauth2provider.com/token/?

grant_type=authorization_code&

code=AUTH_CODE&

redirect_uri=CALLBACK_URI&

client_id=CLIENT_KEY&

client_secret=CLIENT_SECRET

The purpose of this authorization code is to authenticate the POST request above, but due to the nature of the flow, it has to be routed through the user's system. As such, it is inherently insecure. The restrictions on the authorization code, that it expires quickly and can be used only once, are there to mitigate the inherent risk of passing an authentication credential through an untrusted system.

This call, made directly from your server to the OAuth2 provider's server, is the key component of the OAuth2 server-side login process. Controlling the call means you know the call is TLS-secured, protecting it against wiretapping attacks. Including the authorization code ensures that the user explicitly granted consent. Including the client secret, which is never visible to your users, ensures that this request doesn't originate from some virus on the user's system which intercepted the authorization code. If everything matches up, the server returns an access token, with which you can make calls to that provider while authenticated as the user.

Once you've received the access token from the server, your server then redirects the user's browser once more to the landing page for just-logged-in users. It's common to retain the access token in the user's server-side session cache, so that the server can make calls to the given social provider whenever necessary. Of course, the access token should never be available to the user!

There are more details which we could go into: for example, Google will include a refresh token with which you can extend the life of your access token, while Facebook simply provides an endpoint at which you can exchange the short-lived access token they give by default for something longer-lived; these details don't matter to us, though, because we're not going to use this flow.

This flow is cumbersome for a REST API: while you could have the frontend client generate the initial login page, have the backend provide a callback URL, you'll eventually run into a problem: you want to redirect the user to the frontend's landing page once you've received the access token, and there's no clear, RESTful way to do so. Luckily, there's another OAuth2 flow available, which works much better in this case.

In this flow, the frontend becomes responsible for handling the entire OAuth2 process. It generally resembles the server-side flow, with an important exception: frontends live on machines that users control, so cannot be entrusted with the client secret. The solution is to simply eliminate that entire step of the process.

The first step, as in the server-side flow, is registering the application. In this case, the project owner will still register the application, but as a web application; the OAuth2 provider will still provide a client key, but may not provide any client secret.

The frontend provides the user with a social login button as before, and as before, this directs to a webpage the OAuth2 provider controls, requesting permission for our application to access certain aspects of the user's profile. The link looks a little different this time:

https://oauth2provider.com/auth?

response_type=token&

client_id=CLIENT_KEY&

redirect_uri=CALLBACK_URI&

scope=profile&

scope=email

Note that the response_type this time is now token.

This should be the same image we created before

So what about the redirect uri? This is simply any address on the frontend which is prepared to handle the access token appropriately. Depending on the OAuth2 library in use, the frontend may actually temporarily run a server capable of accepting HTTP requests on the user's device; in that case, the redirect URL is of the form http://localhost:7862/callback/?token=TOKEN. Because the OAuth2 server returns a HTTP redirect after the user has accepted, and this redirect is processed by the browser on the user's device, this address is interpreted correctly, giving the frontend access to the token. Alternately, the frontend may directly implement an appropriate page. Either way, the frontend is responsible at this point for parsing the query parameters and processing the access token.

From this point, the frontend can directly call the OAuth2 provider's API using the token, but they don't really want that; they want authenticated access to your API! However, the backend is excluded from the OAuth2 process using this flow, so all it needs to provide is an endpoint at which the frontend can exchange a social provider's access token for a token which grants access to your API.

Why allow this at all, given that giving the access token to the frontend is inherently less secure than the server-side flow? The client-side flow allows a stricter separation between a backend REST API and a user-facing frontend. There's nothing strictly stopping you from specifying your backend server as the redirect URI; the end effect would be some kind of hybrid flow. The issue is that that server must then generate an appropriate user-facing page, and then hand control back to the frontend in some way.

It's common in modern projects to strictly separate concerns between the frontend and the backend: the backend handles all the business logic, and the frontend handles the UI. They typically communicate via a well-specified JSON API. The hybrid flow described above muddies that separation of concerns, forcing the backend to both serve a user-facing page, and then design some flow to somehow hand control back to the frontend. Allowing the frontend to handle the access token is an expedient which retains the separation of concerns. It somewhat increases the risk from a poisoned client, but it generally works well.

This flow may seem complicated for the frontend, and it is, if you require the frontend team to develop everything on their own. However, both Facebook and Google provide libraries which enable the frontend to include login buttons which handle the entire process with a minimum of configuration.

Please have a designer make this diagram pretty

. SERVER FLOW CLIENT FLOW

+-----------------------------+ +-----------------------------+

| Page presents login button | | Frontend presents login |

| to user | | button to user |

+-----------------------------+ +-----------------------------+

| |

+-----------------------------+ +-----------------------------+

| Button click redirects to | | Button click redirects to |

| social auth server | | social auth server |

+-----------------------------+ +-----------------------------+

| |

| +-----------------------------+

| | Frontend starts up a short- |

| | lived web server which |

| | accepts requests at the |

| | callback uri. |

| +-----------------------------+

| |

+-----------------------------+ +-----------------------------+

| OAuth2 provider validates | | OAuth2 provider validates |

| request; redirects user to | | request; redirects user to |

| server-side | | frontend |

| callback url, including an | | callback url, including an |

| authorization code | | access token |

+-----------------------------+ +-----------------------------+

| |

+-----------------------------+ +-----------------------------+

| Server makes REST request | | Frontend makes REST request |

| to OAuth2 provider, | | to your backend, exchanging |

| exchanging authorization | | provider access token for |

| code for access token | | an access token which works |

+-----------------------------+ | on your API |

| +-----------------------------+

| |

+-----------------------------+ +-----------------------------+

| Backend makes calls to | | Frontend makes calls to |

| OAuth2 provider as | | your API; backend calls |

| necessary | | OAuth2 provider as |

+-----------------------------+ | necessary |

+-----------------------------+

Under the client flow, the backend is pretty isolated from the OAuth2 process. Unfortunately, that doesn't mean its job is simple. You want at least the following features:

- Send at least one request to the OAuth2 provider just to ensure that the token that the frontend provided was valid, not some arbitrary random string.

- When the token is valid, return a token valid for your API. Otherwise, return an informative error.

- If this is a new user, create a

Usermodel for them and populate it appropriately. - If this is a user for whom a

Usermodel already exists, match them by their email address, so they gain access to the correct account instead of creating a new one for the social login. - Update the user's profile details according to what they've provided on social media.

So here's the magic: how to get all that working on the backend in two dozen lines of code. This depends on the Python Social Auth library ("PSA" henceforth), so you'll need to include both social-auth-core and social-auth-app-django in your requirements.txt. You'll also need to configure the library as documented here. Note that this excludes some exception handling for clarity. Full code for this example can be found here.

@api_view(http_method_names=['POST'])

@permission_classes([AllowAny])

@psa()

def exchange_token(request, backend):

serializer = SocialSerializer(data=request.data)

if serializer.is_valid(raise_exception=True):

# This is the key line of code: with the @psa() decorator above,

# it engages the PSA machinery to perform whatever social authentication

# steps are configured in your SOCIAL_AUTH_PIPELINE. At the end, it either

# hands you a populated User model of whatever type you've configured in

# your project, or None.

user = request.backend.do_auth(serializer.validated_data['access_token'])

if user:

# if using some other token backend than DRF's built-in TokenAuthentication,

# you'll need to customize this to get an appropriate token object

token, _ = Token.objects.get_or_create(user=user)

return Response({'token': token.key})

else:

return Response(

{'errors': {'token': 'Invalid token'}},

status=status.HTTP_400_BAD_REQUEST,

)There's just a little more that needs to go in your settings (example), and then you're all set:

AUTHENTICATION_BACKENDS = (

'social_core.backends.google.GoogleOAuth2',

'social_core.backends.facebook.FacebookOAuth2',

'django.contrib.auth.backends.ModelBackend',

)

for key in ['GOOGLE_OAUTH2_KEY',

'GOOGLE_OAUTH2_SECRET',

'FACEBOOK_KEY',

'FACEBOOK_SECRET']:

# Use exec instead of eval here because we're not just trying to evaluate a dynamic value here;

# we're setting a module attribute whose name varies.

exec("SOCIAL_AUTH_{key} = os.environ.get('{key}')".format(key=key))

SOCIAL_AUTH_PIPELINE = (

'social_core.pipeline.social_auth.social_details',

'social_core.pipeline.social_auth.social_uid',

'social_core.pipeline.social_auth.auth_allowed',

'social_core.pipeline.social_auth.social_user',

'social_core.pipeline.user.get_username',

'social_core.pipeline.social_auth.associate_by_email',

'social_core.pipeline.user.create_user',

'social_core.pipeline.social_auth.associate_user',

'social_core.pipeline.social_auth.load_extra_data',

'social_core.pipeline.user.user_details',

)Add a mapping to this function in your urls.py, and you're all set!

An illustration here to convey the magic: a wizard opening a lock, maybe

In short, it's magic. Python Social Auth is a very cool, very complex piece of machinery; it's perfectly happy to handle authentication and access to any of several dozen social auth providers, and it works on most popular Python web frameworks, including Django, Flask, Pyramid, CherryPy, and WebPy.

For the most part, the code above is just a very standard DRF function-based view: It listens for POST requests on whichever path you map it to in your urls.py, and assuming you send it a request in the format it expects, it then gets you a User object, or None. If you get a User, it's of the model type you've configured elsewhere in your project, which might or might not have already existed. PSA already took care of validating the token, identifying whether or not a user match existed, creating a user if necessary, and updating user details from the social provider. The exact details of how a user is mapped from the social provider's user to yours, and associated with existing users, are specified by the SOCIAL_AUTH_PIPELINE defined above. There's a lot of detail to how that works, but it's out of scope here; you can read more about it here.

The key bit of magic is the @psa() decorator on the view, which adds some members to the request object which gets passed in to your view. The one of interest to us is request.backend; a backend, to PSA, is any social authentication provider. The appropriate one was chosen for us and appended to the request object because of the backend argument to the view, which gets populated by the URL itself.

Once you have the backend object in hand, it's perfectly happy to authenticate you against that provider, given your access code; that's the do_auth method. This, in turn, engages the entirety of the SOCIAL_AUTH_PIPELINE from your config file. This pipeline can do some pretty powerful things if you extend it, but it already does everything we need with nothing but built-in stages.

After that, it's just back to normal DRF code: if you got a valid User object, you can return an appropriate API token very easily. If you didn't get a valid User object back, it's still easy to generate an error.

One drawback of this technique is that while it's relatively simple to return errors if they occur, it's hard to get much detail about what specifically went wrong; PSA swallows any details the server might have returned about what the problem was. Then again, it is in the nature of well-designed authentication systems to be taciturn about error sources. If an application ever tells a user "Invalid Password" after a login attempt, that's tantamount to saying "Congratulations! You've guessed a valid username."

In a word: extensibility. Very few social OAuth2 providers require or return exactly the same information in their API calls in exactly the same way; there are all kinds of special cases and exceptions. Adding a new social provider once you've got PSA already up and running is a matter of a few lines of configuration in your settings files; you don't have to adjust any code at all. PSA abstracts all of that out, so that you can focus on your own application.

Good question! unittest.mock is not well-suited to mocking out API calls buried under an abstraction layer deep inside a library; just discovering the precise path to mock would take substantial effort. Instead, because PSA is built atop the Requests library, we use the excellent Responses library to mock out the providers at the HTTP level. A full discussion of testing is beyond the scope of this article, but a sample of our tests are included here. Particular functions to note there are the mocked context manager and the TestSocialAuth class.

The OAuth2 process is a detailed and complicated thing with a lot of inherent complexity. Luckily, it's possible to bypass much of that complexity by bringing in a library dedicated to handling it in as painless a way as possible. Python Social Auth does a great job at that; we've demo'd a Django/DRF view which utilizes the client-side, implicit, OAuth2 flow to get seamless user creation and matching in only 25 lines of code.

Naturally, there's always a better way, and we all love dogshedding. Share your thoughts in the comments below!