-

-

Notifications

You must be signed in to change notification settings - Fork 820

New issue

Have a question about this project? Sign up for a free GitHub account to open an issue and contact its maintainers and the community.

By clicking “Sign up for GitHub”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy statement. We’ll occasionally send you account related emails.

Already on GitHub? Sign in to your account

Authorization #313

Comments

|

Another possible avenue (as suggested by @fubhy) rather than magic const permissionMap = {

Post: {

notes: (resolverExecuter, args, context) => {

if (!isLoggedIn(context.user)) return false;

// Execute the resolver

const data = resolverExecuter();

return isAuthor(data);

}

}

}

let executed = false;

let data;

const resolverExecuter = () => {

data = field.resolver();

executed = true;

return data;

}

if (field.permission(resolverExecuter, args, context)) {

if (!executed) data = field.resolver();

return data;

}That way the developer has full control over when to execute which validations and which data they need, rather than relying on magic properties. |

|

Hey @mxstbr, I think that's a really cool idea. I like the first syntax for defining it (permissionsMap), because it's much easier to read. You're right that something like The I think this could look really neat, and would be great to have in graphql-tools. Do you have time to help us make it happen? Another approach would be to actually push permissions down to the model layer (which is what FB does internally). We're thinking about a next version of graphql-tools that would organize schema and resolvers a little differently and lets you define the models along with it. I think @thebigredgeek has been thinking about stuff like this, so he might have some thoughts to share here. Also, checking permissions is just a form of validation. Some validations (as you pointed out) can be done statically, some can only be done during execution. It would be really neat if the static ones could be run before the query even begins execution. I recently had a conversation with @JeffRMoore about this, so it would be really interesting to have his take here as well. I think it could be relatively easy to create a validation rule that checks "static" permissions before executing if we mark them somehow. |

The second syntax is still the same, except rather than having

I'm exactly 0 familiar with the codebase, but I'd be happy to dig in seeing as I need to add permissions to my server. 😉 Let's wait and see what @thebigredgeek and @JeffRMoore have to say! |

|

Yeah those two have been thinking about this a lot! |

|

I saw @mxstbr tweet about this thread and wanted to chime in with how we do auth on the bustle graphQL API. I extracted the code below but this is the general setup:

import {

defaultFieldResolver,

GraphQLID,

GraphQLNonNull,

GraphQLError,

GraphQLObjectType,

GraphQLString,

GraphQLSchema

} from 'graphql'

const User = new GraphQLObjectType({

name: 'User',

fields: {

id: {

type: new GraphQLNonNull(GraphQLID)

},

email: {

authorize: (root, args, context) => {

if (root.id !== context.currentUser.id) {

throw new GraphQLError('You are only authorized to access field "email" on your own user')

}

},

type: new GraphQLNonNull(GraphQLString)

}

}

})

// Walk every field and swaps out the resolvers if an `authorize` key is present

function authorize (schema) {

Object.keys(schema._typeMap).forEach((typName) => {

const typ = schema._typeMap[typName]

if (!typ._fields) {

return

}

Object.keys(typ._fields).forEach((fieldName) => {

const field = typ._fields[fieldName]

if (field.authorize) {

typ._fields[fieldName] = wrapResolver(field)

}

})

})

return schema

}

// wrap resolver with authorize function

function wrapResolver (field) {

const {

resolve: oldResolver = defaultFieldResolver,

authorize,

description: oldDescription

} = field

const resolve = async function (root, args, context, info) {

await authorize(...arguments)

return oldResolver(...arguments)

}

const description = oldDescription || 'This field requires authorization.'

return { ...field, resolve, description, authorize, isAuthorized: true }

}

const query = new GraphQLObjectType({

name: 'Query',

fields: {

user: {

type: User,

args: {

id: { type: new GraphQLNonNull(GraphQLID) }

},

resolve: (root, args, context) => context.db.find('user', args.id)

}

}

})

export default authorize(new GraphQLSchema({ query })) |

|

Thanks of chiming in, that's remarkably similar to what I'm thinking! 👌 Seeing that example of using const isLoggedIn = (_, _, { user }) => user;

// Check if the user requesting the resource is the author of the post

const isAuthor = (root, _, { user }) => user.id === root.author;

const permissionMap = {

Query: {

post: isLoggedIn

},

Post: {

__self: isLoggedIn,

notes: isAuthor

}

} |

|

What are the benefits to using a permissions map compared to, say, composable resolvers that simply throw errors if state preconditions aren't met? This is what I am already doing and it works really well. I don't know if additional API surface area is necessary to solve this challenge |

|

Sure, one could do that (it's what @fubhy is doing right now and suggested I do) but I found it makes the whole codebase more complex, unnecessarily so. You can't write resolvers inline anymore, you have to understand how to compose functions (you and I do, but why do the juniors in your team have to?), permission functions are this limbo that kind of live with resolvers but kind of don't etc. (in my opinion, of course. Happy to be proven otherwise!) It also means you have to define totally unnecessary resolvers for scalar types, as const resolverMap = {

Post: {

// post.notes is just a String, but now I need to define a custom resolver just to add permissions even though GraphQL could get this scalar type perfectly fine without the custom resolver

notes: (root, args, context) => isAuthor(root, args, context) && root.notes,

},

};Resolvers are a mapping from a path ( Now, one could argue that this means permissions should be pushed down to the model layer (skinny controller, fat model in traditional MVC-speak) and handled there, but that's unwieldy because you have to pass the context and root of the resolver down to the model for every. single. query. in every. single. resolver: const Post = require('../models/Post');

const resolverMap = {

Post: {

// One would have to pass { root, context } to every query 👇 in every resolver

notes: (root, args, context) => Post.getNotes(args.postId, { root, context }),

},

};That (again) adds a lot of complexity when working in the codebase because one has to remember which queries get passed that and which don't, and that you have to pass them all the time. That's my logic and why I think permissions should live on a separate layer from resolvers and models. I don't know if |

Why would the root be needed, when resolving the data? I mean, I can only imagine the user (user context) being needed, similar to what Dan Schafer points out in his talk about how Facebook goes about authorization. Scott |

|

Like @southpolesteve, I saw @mxstbr tweet about this thread. I think the solution given by @southpolesteve is the way to go. However, this is too much dedicated to Authorization. This new layer should be more generic and be able to execute an array of functions whatever their purpose. To give you an example, on a mutation, sometimes you have to format the incoming data or check if the email is available or not. In this case, you have to execute functions which are not specific to Authorization and we have to execute these functions before the query/mutation resolver. IMO, we have two levels:

I kept the exact same example but I replaced the Note: I haven't tested this code but it's just to give you an idea of how we could implement it. import {

defaultFieldResolver,

GraphQLID,

GraphQLNonNull,

GraphQLError,

GraphQLObjectType,

GraphQLString,

GraphQLSchema

} from 'graphql';

import {

isAuthenticated,

isOwner

} from './policies';

const User = new GraphQLObjectType({

name: 'User',

fields: {

id: {

type: new GraphQLNonNull(GraphQLID)

},

email: {

policies: [isOwner],

type: new GraphQLNonNull(GraphQLString)

}

}

})

function policies (schema) {

Object.keys(schema._typeMap).forEach((typName) => {

const typ = schema._typeMap[typName]

if (!typ._fields) {

return

}

// Be able to execute functions before the query/mutation resolver.

if (typ.policies) {

typ.resolve = wrapResolver(type);

}

Object.keys(typ._fields).forEach((fieldName) => {

const field = typ._fields[fieldName]

if (field.policies) {

// Be able to execute functions before the field resolver.

typ._fields[fieldName] = wrapResolver(field);

}

})

})

return schema

}

// wrap resolver with authorize function

function wrapResolver (field) {

const {

resolve: oldResolver = defaultFieldResolver,

policies

} = field

const resolve = async function (root, args, context, info) {

// Execute the array of functions (policies) in series.

for (let i = 0; i < policies.length; ++i) {

await policies[i](...arguments);

}

return oldResolver(...arguments)

}

return { ...field, resolve, policies}

}

const query = new GraphQLObjectType({

name: 'Query',

fields: {

user: {

type: User,

args: {

id: { type: new GraphQLNonNull(GraphQLID) }

},

policies: [isAuthenticated],

resolve: (root, args, context) => context.db.find('user', args.id)

}

}

})

export default policies(new GraphQLSchema({ query }))The policy (function) could look like this: // ./policies/isAuthenticated.js

export default (root, args, context, info) => {

if (root.id !== context.currentUser.id) {

throw new GraphQLError('You are only authorized to access field "email" on your own user')

}

} |

What about only the author of a post being able to read the notes? (see the OP) Can't do that based on the context and the args alone, you need to have the data for that.

I like that idea, rather than being specific to permissions it could be a generic validation layer, no matter if format or permissions or anything else! The API could still stand as discussed above, except renaming it to |

Hmm... I would have thought the data would be outside the resolver, like Facebook does with DataLoader. Scott |

|

Sure, that might be the case, but I feel like if we have the data why not pass it in and let people decide how to handle it? Also, not everybody might be using DataLoader etc. (it's also a pretty fine detail of a pretty big API 😉) |

Yes, it makes sense to use a more generic name. Based on my personal experience, it was a nightmare to pass the context into the DataLoader because it only accepts one argument... Despite this, I agree with @mxstbr if we have it, we should probably pass the data in the context and let people decide how to handle it. |

|

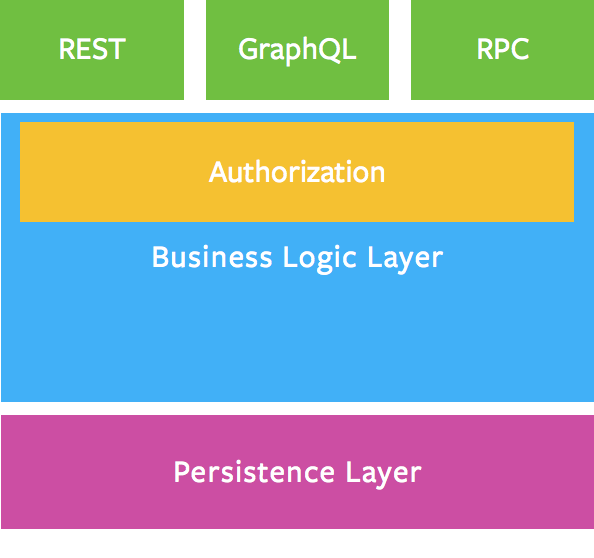

Pulling back and looking at this from an overarching 1000 mile up in the sky view, I'm of the opinion that the authorization should be on top of the business logic and not in the API. So, this goes along with what @helfer said in his first post with:

My main reasoning for this is based on the assumption that at some point in the evolution of GraphQL (and I'll be money Facebook is doing it now), I believe the creation of the API will be mostly an automated process. Having permissions mixed in the API layer would make that automation programming a lot more difficult. This graphic is best practice according to the makers (and how I see it too): Also, in this great article from @helfer, he also says this:

I'd also actually improve number 2.

Which basically means, the authorization could be available for any type of API (as the image shows too) and not be concerned with data fetching concerns. Such "business details" as authorization is opinionation and again, should be avoided in any API. Sure, it means no standard for authorization within (Apollo's) GraphQL implementation. But, that is, again in my opinion, a good thing. What should first be agreed upon is where authorization should take place or where it shouldn't. I say, it should definitely not be within the GraphQL API layer. That is just my (last) 2 cents. 😄 Scott |

|

In that graphic you posted there's two layers:

The "persistence layer" are the models, they persist stuff to the database. Pushing the business logic into that seems to even be discouraged by that graphic, as far as I can tell. What I'm trying to figure out here is basically where that "business logic" layer lives—I don't think resolvers are the right place for that, models apparently aren't either, which leaves us with.. not much 😉 That's why I think adding an explicit API to |

|

To me models are only the business logic. Theoretically, a good model system should not know any details about the databases/ data sources it connects to. Because, one day you might be using MySQL, then realize some other database(s) are even better solutions. You'll notice, any good ORM can connect to multiple SQL databases. This abstracted out connectivity to any database/ source is the persistence layer. It is also the layer where a tool like DataLoader would do very well. 😄 Obviously, we're talking about a lot of abstraction and for a relatively simple system, it is probably a good bit of overkill. However, this separation of concerns is how I believe (and Facebook also teaches) it needs to be, if your system is going to be future-proof. Scott |

|

I want to weigh in here, because this has the danger of setting up some hasty de facto standards, and hasty is the last thing we should be when it comes to security. I've built GraphQL servers on top of existing micro-service platforms, and in new projects where GraphQL and "the platform" live in the same app instance. Once thing i've never done is treat the GraphQL server as trusted. I can make every API that my resolvers call into a public one without breaking the security of my system. In the case of the existing systems, this was necessary (all our APIs are externally accessible); in the new systems it just seemed like a best practice. In both types of implementation (micro-service vs monolith), the way i've done the GraphQL server has been identical - resolvers do some relatively trivial unpacking they're parameters, than call a function that's been defined elsewhere as the interface to "the business layer". Everything behind those functions can change as much as it likes, I can switch databases and require no code changes to my GraphQL server. This is good. Permissioning is a concern that all developers need to think about, and I think most will be nervous about having the outermost layer of the stack be responsible for handling it. However, there's also talk of pre/post behaviour when evaluating Types. i.e. whenever I have a Product, regardless of how I get to it. There's value in exploring some ideas here, but in a more general way than specifically tackling permissions or validation. I looked into this very thing when trying to find a generalised solution for the look-ahead problem (i.e the final part of what I talk about in this article: https://dev-blog.apollodata.com/optimizing-your-graphql-request-waterfalls-7c3f3360b051). Ultimately I found other ways to do it (I wrapped dataloader), and felt better about not trying to bolt on additional unnecessary API to my GraphQL server, but I still think it's worth playing around with the idea to see what other utility it could bring. One other parting thought. I believe the sweet spot of GraphQL is largely as @smolinari has pointed out. It takes relatively little effort to get to this type of separation, even in a monolithic codebase, and the benefits it brings for long-term maintainability are real. I think effort would be better spend producing examples of medium-sized codebases that follow these patterns. |

You're right, good call!

This is a very interesting point. You're right that we loose this property with the current API suggestion, I agree that's suboptimal. I don't think I agree that this means we shouldn't think about adding an API for this, it just needs to be a different one. I'd really like to avoid having to write a ton of resolvers just for validation purposes because the default one would suffice normally. (e.g. I also want an abstraction that keeps validation separate from the general "business logic" layer rather than randomly sprinkled throughout the codebase. I'm pretty sure this makes it easier to figure out what's not being validated correctly/what's been forgotten and also make it easier to spot bugs since every responsibility (types, mapping types -> models, database handling, permissions/validation,...) is handled at a specific place.

If I have validations somewhere inside my models (or not), I have to start digging a lot more to figure out which specific LoC is broken. I don't have any good ideas for other APIs right now, but I think it's still worth finding one? |

|

https://github.com/thebigredgeek/apollo-resolvers < This has made authorization a very simple matter for me and my team, at least with Monoliths. That said, when working with microservices, I think it often makes sense to delegate authorization logic to the service responsible for the domain of a given resource, so the GraphQL server should probably only care about authentication and perhaps high-level authorization (is the user logged in or not, what is the high-level role of the user, etc). I think you can accomplish more granular authentication rules by simply passing user data (such as their ID) to your data layer (models + connectors OR separate services, depending on your paradigm) and letting said data layer decide what the user should and shouldn't be able to do. Ultimately, I think this conversation is more about how to handle authorization within the domain of GraphQL and not within the domain of the data layer, so I believe a line has to be drawn regarding best practices. The challenges facing GraphQL authorization are congruent with the challenges facing RESTful authorization, with the exception of data traversal restrictions that are necessary in GraphQL but often not with REST. I think we should avoid reinventing the wheel, treat GraphQL as a transport and traversion DSL, and reuse as many paradigms from the REST world as possible. |

|

@AndrewIngram I think it's good to bring that up - I do think it's valuable to explore what other paradigms might look like, though.

I agree we should make sure that there is some consensus among a wide range of people before this moves into the sphere of being some kind of recommendation or best practice, but I think that always starts with a discussion that considers a wide range of approaches. |

|

Another thing to consider - Even if you decide not to handle permission checks themselves in GraphQL, you'll definitely want to handle the effects of them. Much like I prefer to handle validation errors from mutations as part of the schema design itself (I prefer reserving error handling for actual errors, not expected validation failures), a similar argument could be made for failed auth checks. Let's say we have a screen on our app, and the data is fetched via a static query (as is becoming best practice), there may be some parts of that data that are only accessible to us when we have the right permissions. Schema-wise I think it's messy to just allow those parts of the schema to be nullable, because it forces us to overload what null means. I tend to advocate going modelling auth restrictions into the schema itself. type User implements Node {

id: ID!

username: String!

articles: [Article]

private: RestrictedPrivateUser

}

type PrivateUser {

email: String

secret: String

}

type InsufficientPermissions {

message: String!

}

union RestrictedPrivateUser = InsufficientPermissions | PrivateUserI appreciate that this is a lot more verbose than just allowing email and secret to be nullable (and I hope that as graphql evolves we gain a more expressive type system to allow things like anonymous unions). But If I were to move those fields onto User itself, a null value for either of them doesn't tell me enough - i'm forced to look at the query error to figure out what the null means. But why is this an issue? Well mainly because I don't considered expected behaviour to be an error. Remember, we have a screen powered by a single static query, a query that works fine for one user might be full of errors for another, and for a permission-heavy app this might mean that a significant amount of front-end complexity is dedicated to pulling things out of the errors object. Another reason I like this approach, is that it forces the front-end developers to handle these cases, much like we'd be doing if we were using a language like Elm. It's a total pain in the arse, but it leads to better software. |

|

@AndrewIngram don't you have to implement a lot of duck typing on the client to properly handle whether or not a |

|

You'd just query for and branch on |

|

Ah interesting. Have you had any issues working with that kind of model? I've been keeping all of my errors in the errors array, but I've been thinking about placing them in context-specific places for a while. Can you speak on benefits as well? |

|

It's mainly inspired by patterns I see in more functional languages, where most errors are treated as data rather than as a bailout. It feels like a better way of encouraging API consumers (in our case, client app developers) to properly handle the various ways things can go wrong. Why model into the schema rather than the errors array? Essentially, you're going to end up with a variety of error type; timeouts, missing data, failed auth, form validation, each of which is likely to want to evolve over time to capture more nuance. A data structure suitable for modelling a timeout is unlikely to be identical to one suitable for modelling a form validation error. When we just throw all of these into the errors array, we're requiring that clients are aware of all the various types of errors and what they look like - otherwise how do they pull the data out? You end up with your own ad-hoc mini schema just for errors, but largely separate from the very technology aimed at allowing client-data coupling to be done cleanly - i.e. GraphQL. This is why I prefer the errors array to represent errors within the GraphQL server itself, rather than errors exposed by the underlying data model. Drawbacks? It's initially a lot more work to do it this way, the downsides of using the errors array aren't initially obvious (and you may reach the point where it's an issue). It can also be awkward to have to wrap scalars in object types just so they can be used in a union. If you want to move fast and break things, you're going to be very resistant to the approach i'm suggesting. I've mainly only tried this with toy problems, where it's the most painful (I don't have a large suite of error types built up in my schemas) to implement, so my feeling that it gets easier over time is based on inference rather than real-world experience. |

|

To get back to the original conversation about authorization, I think there's a lot of value in having a clear place where permissions checks happen. I agree that they're only one kind of query and parameter validation, but they're an extremely common kind so I think it helps to give guidance around that. @AndrewIngram 's point about many applications already having authorization in some backend or other is certainly true, but I think we shouldn't take architecture choices made prior to the addition of GraphQL as evidence that this is the right thing to do in GraphQL. I would argue that the opposite is true. Taking GraphQL as a given (which makes sense for a repo called graphql-tools), we should figure out a good way of doing authorization. As mentioned earlier in the conversation, I think it makes sense to check permissions in a layer that's separate from resolvers, and also separate from loading data from the backends. Why? Because that gives you maximum flexibility when it comes to caching. Writing a permissions-aware caching layer is (in my humble opinion) a fool's errand. Assuming that we want the cache to live as close to the edge as possible for performance reasons, the cache should be in or near the GraphQL layer, and permissions should be checked after retrieving items from the cache (with some exceptions where it's trivially possible to determine permissions without materializing the object). But rather than just talking about it, I think it's most useful if we try out our different hypotheses with a couple of code examples like @mxstbr 's PR #315. |

|

To clarify, my points aren't based on the assumption of building GraphQL on top of an existing system, they could apply equally to a new system. It's more based on the assumption that GraphQL isn't the exclusive route for data access. What i'm arguing against is an explicit API for permissions (or input validation, but I find it easier to buy in to that one) in graphql-tools. @mxstbr's solution could easily be implemented as a generic |

|

I went ahead and created a rough implementation of the API that was suggested above in #315. This is what it looks like: # A written text by an author

type Post {}

type Query {

# Get a post

post(id: ID!): Post

}

schema {

query: Query

}makeExecutableSchema({

validations: {

Query: {

// Returning false here will not execute the resolver when post is queried

// Can also return a Promise if necessary

post: (root, args, context, info) => true

}

}

})

I think that works pretty well with what @AndrewIngram is saying, since it's not explicitly for permissions, it's just generally "Do you want to execute the resolver at this field yes/no", right? |

|

Oh, it read like you were saying this is how they implement it specifically with GraphQL, rather than the pattern of rule-based permissions in general (which is the only way i'm familiar with, how else would you do it?). |

|

I would like to add my 5 cents into this great discussion. The concerns raised here are beyond authorization and validation needs and this is really good. GraphQL schema is a contract between API implementation and users of the API. This contract however also specifies properties (field names, types, etc) of entities used in the implementation, for example The developer might want to express some application-specific properties of If this option to attach metadata to schema is not available, the developer will have to:

GraphQL decorators from the first look seem like a good way to attach metadata to schema and then process it by application. Here I think I share vision with @JeffRMoore We certainly want all the GraphQL tools to continue working when we attach metadata to schema. And it looks doable, because these tools need not bother about this metadata at all. At the same time we want to fully express properties of schema |

|

One other perspective to consider: Schema languages exist to insure conformity to a specification of data structure. Schemata are contracts between producers and consumers that essentially say: "If you want to request data from, or wish to save data to my service, you must do so in this manner." Injecting identification/authentication into this contract is pulling business logic where it doesn't belong, IMO. That being said, what is the role of a resolver? In the MVC world, I would categorize it as a Controller, as it augments and marshals data to and from the Model to match the View's (GrapqhQL client's) request. Logic of resolvers should be left to this task. I personally prefer the middleware approach, where you can inject authentication as a stage in request propagation, so having Something along these lines: const schema = `

type User {

id: ID!

posts: [Post]

}

type Post {

title: String!

content: String!

owner: ID!

}

input PostInput {

user: User!

title: String!

content: String!

}

`

const query = `

type Query {

post(id: ID!): Post

}

`

const mutation = `

type Mutation {

addPost(input: PostInput!): Post

}

`

const resolverMiddleware = {

User: {

posts: async ({ownerId: id}) => models.post.getAll(ownerId)

},

Query: {

post: async (_, {id}) => models.post.get(id)

},

Mutation: {

addPost: async (_, {input}) => {

const post = models.post.add(input)

models.user.addPost(post)

return post

}

}

}

const authMiddleware = {

Query: {

post: async (source, {id}, ctx, next) => {

if (!isLoggedIn(ctx.tokens) || models.post.isPrivate(id)) {

throw new GraphQLAuthError("You do not have permission for this request.")

}

return await next(...arguments)

}

}

Mutation: {

addPost: async (source, {input}, ctx, next) => {

if (!isLoggedIn(ctx.tokens) || !models.post.isOwner(input.id, ctx.tokens.authToken.user)) {

throw new GraphQLAuthError("You do not have permission for this request.")

}

return await next(...arguments)

}

}

}

const makeExecutableSchema({

schema,

query,

mutation,

middleware: [authMiddleware, resolverMiddleware]

}) |

|

Adding yet another 2c to this conversation, but I am of the sentiment that authorization does not belong as part of the schema, and rather the business layer handles this. I'm currently handling GraphQL authorization in three ways:

So far, I haven't really found any issues with this approach, other than possibly performance (but that's a different topic). With the approach above, our REST API and GraphQL API are basically utilizing the same authorization logic. |

|

The suggestion above is exactly what I think should be absolutely avoided. It has nothing to do with being a Gateway into business logic. The suggestion is adding business logic into the Gateway. And, that is a total NO GO from my perspective! Scott |

|

Then perhaps the middleware approach is better, as it leaves opinionative design choices up to the developer. |

|

Another totally different approach is to make use of the Pipes and Filters Design Pattern. A pipeline is made out of processing filters (in this case implemented as promisses or async functions) and the output of one filter is the input for the next filter (one parameter). With this approach all the logic is in the resolver (maybe going against previous posts in this issue). The p-waterfall npm package is one implementation of this pattern. Then you can have for instance: import processingPipe from 'p-waterfall';

........

........

async function pipelineResolver(parent, args, ctx, ast) {

// Build one parameter accepted as input and returned by each filter

let input = {parent: parent, args: args, ctx: ctx, ast: ast};

let filters = [

value => sanitize(value),

value => audit(value),

value => authenticate(value),

value => authorize(value),

value => validate(value),

value => operation(value) // The real work the resolver is supposed to do

];

return await processingPipe(filters, input); |

|

I thought I'd share my approach to authorization while developing an acl plugin for my project graphql factory which uses the In factory, there are before and after resolver function middleware hooks. For the acl plugin I take advantage of the before hook to analyze the fieldNodes to create a list of request paths Request paths can contain schemas, mutations, queries, selections, and arguments. An example would be

where Additionally inherited permissions are specified with an would look like This list is checked against the user id of the requestor (passed in If the user does not have the correct permission on any of the requested fields, the request is considered unauthorized and the before hook/middleware immediately returns an error result without executing the resolver function. Additionally explicit denies which take priority over allows are achieved by prefixing the request path with a |

|

@bhoriuchi i completely agree with you with use ACL for graphql permissions, actually ACL achieve all requirements business application grade, i works for many years for usage in every day that approach and i was happy when i saw first time graphql it was easy to see schema as in ACL your if u have aco based on b-tree implementation you are in home actually cause ACL is super designed and you can do under access list: check is ARO - acces request object (can be user,group, even device... whathever with linked to authorised object - certificate, user_id, jwt_payload) basically with use process gql request with function waterfall @leoncc idea and place inside one more i thought i consider generate schemas per user with limit avaiable resources but i dont thing is worth of it there is many implementation on os layer, osi network, web, frameworks, languages first time i used ACL in @cakephp project - acl plugin :) 🍺 |

|

Posts that have resonated the most with me:

My two bits:

This kind of functional composability support was a big win for Apollo Client 2.0 when it provided Apollo Link for client creation; it would be great if graphql-tools had something like that for server creation. |

|

My last comment was in July, pertaining my experience so far. Circling back now in Nov, I've since built two more GraphQL APIs in Phoenix (Elixir) and Symfony (PHP), both used in production environments (as well as a few smaller sandbox tests in Node, etc.). I can say that my last comment has worked well. To recap and extend a bit (note, this is higher level than apollo, or graphql-tools):

|

|

Excellent discussion above, really appreciate it. I found this discussion because an endpoint I have that was completely protected by a user session now needs "anonymous" user access. I need to forbid all mutations for this anonymous user and allow about 90% of the objects to be queried with existing ACL logic intact. Currently users not authorized are forbidden from doing anything (at the server layer), but that won't work anymore. I really don't want to write the logic into all my ORM layer ACLs to forbid mutation access when viewer is falsey, I want to do it once. However, my ORM layer doesn't have middleware. So I was hoping to do this in my graphql layer. But as noted above graphql is the wrong layer to do this, and furthermore, the fact that my ORM layer doesn't have middleware isn't your fault, it's my fault :-) thanks for warning me off from a solution that will be problematic in the long term, if for example I add a RESTful API on top of my ORM layer, or a different schema of graphQL for a newer version of the API, or ... TL;DR: Keep ACLs in the business logic. If your business logic isn't extensible, fix that problem in the business logc. |

|

I think if you want to do something simple like "forbid all mutations for X user" then it might be reasonable to do that in GraphQL, maybe? But there's a big risk that the rule will get more complex over time :] |

|

I have been using resolver middleware in my gateways, and I have to say that applying authentication and authorization functionality using resolver middlewares has been quite a good experience. I use a Koa-style pattern for my middlewares, so I can run logic both before ('route based') and after ('result based') the actual resolver. To me, this is a clean way of implementing this functionality. When exposing an existing GraphQL endpoint in a Gateway, there's really no other place to put this logic, and I don't see why this would be considered bad practice at all. To me, resolver middleware is equivalent to the router-level middleware in your traditional Express/Koa web server, so it's a natural fit. |

|

There's also some wisdom that says router middleware isn't a good place to put permissions logic though, right? At least back when I used Rails the mantra was "thin controllers, fat models", and all permissions was recommended to be done in the model, not the route handlers/controllers. |

|

@stubailo What would the 'model layer' be when working with existing GraphQL endpoints and schema stitching? |

|

With schema stitching, that probably means in the underlying GraphQL services is best, and with GraphQL subscriptions you call your regular data loading code, right? I guess what I mean is that your security shouldn't be transport or API dependent, in my opinion. Since there are often different ways to access the same data (for example, an object showing up in a subscription and a query shouldn't require two separate security rules) |

|

@stubailo I don't agree with you on that. I'd like to compare it to having a bunch of internal REST API's that you are exposing through a Gateway. The REST API's themselves don't implement user-level security. The Gateway that exposes these as a public API needs to do that, as the API's themselves might not even share the (same) concept of a 'user'. This is a scenario where it's very common to have this logic in the Gateway. I see the same happening with GraphQL endpoints. You can't always control the implementation of the GraphQL API you are exposing (more commonly not actually). |

|

That's a great point - I think there isn't a clear answer yet, so we should consider all the options for sure. |

|

And as I write my code, and find yet another internal API that wasn't checking for a valid viewer before writing. So bug prone. I wish I had the middleware to just prevent writes by all non-valid viewers. I note I didn't say where the middleware should go... |

|

Hey 👋 I created a helper tool called https://github.com/maticzav/graphql-shield |

|

Hey everyone! I'm going to close this issue, as it's been stale for a while (and frankly, a lot to digest as we try to clean up this repo). I believe many of the issues raised in here may actually be solvable using schema directives, since they are as customizable as needed, and still leave auth at the schema level if that's something you want. |

Authorization in GraphQL is (as noted by @helfer in this post) currently not a generally solved problem. Everybody has their own, custom solution that works for them but there's no general-purpose solution/library for it. (as far as I can tell)

I think

graphql-toolsis uniquely positioned to fill that hole in the community. Permissions are naturally bound to the schema of the requested data, so to me it feels like a natural fit forgraphql-tools. (note that this is just an idea, wanted to kick off a discussion)Imagine a simple type like this:

There's two types of permissions I want to enforce here. One of them I'm able to tell without running the resolvers first (only readable by the logged-in user), for the other I need the data from the database so they have to run after the resolvers. (only accessible by the author)

I could imagine an API like this working out well:

Similar to

resolversthispermissionMapwould map to the schema:Depending on if you return a truthy or a falsey value from these functions folks get access or a "Permission denied" error. The functions get the same information as resolvers. (i.e.

obj,argsandcontext)This works for the pre-database case (only logged-in users should be able to access), since I could do something like this:

Now the issue is post resolver permission functions. I don't have a good idea how to handle these right now, but maybe something like this could work where each "path" has two magic properties (

.pre,.post) which run those functions before and after the resolver:What do you think? Any previous discussions I'm missing?

The text was updated successfully, but these errors were encountered: